Fibrilación auricular

La fibrilación auricular (FA) es la arritmia más frecuente en la práctica clínica. Su incidencia aumenta de forma significativa con la edad y con la coexistencia de cardiopatía (valvulopatía, cardiopatía isquémica, cardiopatía hipertensiva, enfermedad pericárdica, cirugía cardíaca y anomalías congénitas como la comunicación interauricular). Aunque se ha considerado una arritmia benigna al no estar asociada de forma inmediata a la muerte súbita, diversos estudios epidemiológicos han demostrado que duplica la mortalidad y que conlleva una elevada morbilidad, relacionada sobre

todo con el desarrollo de insuficiencia cardiaca y de tromboembolia arterial (p. ej., el riesgo de ictus es cinco veces superior). La taquicardia mantenida puede producir un empeoramiento de la función sistólica ventricular (taquimiocardiopatía). La insuficiencia cardíaca es un factor de riesgo para desarrollar FA. La disfunción sinusal y el síndrome de Wolff-Parkinson-White presentan con frecuencia episodios de FA. El hipertiroidismo, las enfermedades pulmonares crónicas y agudas, el síndrome de apnea obstructiva del sueño (SAOS), el alcohol, la electrocución, la cirugía torácica, las infecciones severas y la diabetes mellitus, son causas de FA no cardíacas. En un 30%-40% de los casos la FA no se asocia a cardiopatía (FA aislada o idiopática). Existen crisis de FA en relación con predominio simpático, frecuentemente en pacientes con cardiopatía asociada; o parasimpático: la FA vagal se observa en jóvenes varones sin cardiopatía, asociándose a bradicardia sinusal fisiológica nocturna o posprandial.

La FA se caracteriza por un ritmo auricular muy rápido y desorganizado, ocasionado por múltiples focos de reentrada, que no produce actividad mecánica eficaz. Electrocardiográficamente se manifiesta por ondas irregulares muy rápidas (ondas f) que sustituyen a las ondas P del ritmo sinusal normal, siendo más visibles en las derivaciones precordiales V1 y V2. La respuesta ventricular es irreguiar, y es generalmente rápida en los casos de FA paroxistica. y adecuada en la FA crónica estable (con frecuencia como consecuencia del tratamiento farmacológico). Cuando se observa una fibrilación auricular con QRS rítmicos y lentos se debe sospechar bloqueo AV completo y ritmo de escape, y se debe descartar intoxicación digitálica si el paciente estuviera tomando digoxina.

Clínicamente, la FA puede ser asintomática (descubierta casualmente) o manifestarse como palpitaciones, dolor torácico, disnea, cansancio y/o intolerancia al esfuerzo. La sintomatología varía según la frecuencia cardíaca, la duración de la arritmia y la presencia o no de cardiopatía estructural. En muchas ocasiones la primera manifestación puede ser una complicación embólica. El síncope como síntoma de FA es infrecuente, asociándose, cuando aparece, a enfermedad del nodo sinusal o a obstrucción del tracto de salida del ventrículo izquierdo (estenosis aórtica, miocardiopatía hipertrófica obstructiva). La FA rápida puede, a su vez, provocar una taquimiocardiopatía. o la muerte súbita en el caso de pacientes con vías accesorias.

El tratamiento farmacológico de la FA persigue los siguientes objetivos generales:

1. Control de la respuesta ventricular: alcanzar y mantener una FC que asegure el control de los síntomas relacionados con la arritmia, permita una correcta tolerancia al esfuerzo y evite la aparición de complicaciones a largo plazo, como la taquicardiomropatía.

2. Restauración del ritmo sinusal en los pacientes susceptibles.

3. Prevención de recurrencias en pacientes con FA paroxistica, o persistente cardiovertida.

4. Profilaxis de la enfermedad tromboembólica arterial.

A continuación se revisan cada uno de estos aspectos:

A. Control de la frecuencia cardíaca en la FA paroxistica, FA persistente y FA permanente

Se considera aceptable una FC < 90 Ipm en reposo y < 115 Ipm durante el ejercicio. Para tal fin pueden emplearse alguno de los siguientes fármacos:

1. Betabloqueantes intravenosos u orales:

propranolol intravenoso, o atenolol, bisoprolol o sotalol vía oral.

2. Antagonistas del calcio no hidropíridínicos: diltiazem o verapamilo intravenosos o v.o.. como fármacos iniciales o como alternativa a los betabloqueantes si estos están contraindicados (hiperreactividad bronquial, vasculopatía periférica sintomática). Se deben evitar ambos grupos (puntos 1 y 2) si existe insuficiencia cardíaca aguda o hipotensión arterial. 3. Digital: tiene efecto más tardío, incluso si se administra por vía intravenosa, y es menos potente. No controla eficazmente la frecuencia cardíaca durante el esfuerzo; es útil en la FA asociada a insuficiencia cardiaca, o cuando se contempla

asociar a betabloquentes o a calciantagonistas sí existe difícil control de la frecuencia cardiaca. Se puede utilizar en monoterapia en personas ancianas con un nivel de actividad reducida; en este segmento etario debe vigilarse especialmente la posibilidad de intoxicación digitálica (las cifras de creatinína plasmática no reflejan el filtrado glomerular real -disminuido- de estos pacientes). 4. Otros: amiodarona intravenosa, en caso de que los fármacos anteriores no consigan controlar la frecuencia cardíaca. En los casos (poco frecuentes) de difícil control de la frecuencia cardiaca, se puede considerar la indicación de técnicas invasivas, como la ablación del nodo auriculoventricular con la implantación de marcapasos definitivo.

Clasificacion de la fibrilacion auricular siguiendo las recomendaciones de las sociedades americana y europea de cardiología.

FA secundariaCuando la FA es consecuencia de una causa aguda (infarto agudo de miocardio, pericarditis, cirugía). En estas ocasiones, el problema principal es el control de la enfermedad de base. La arritmia es un problema secundario y su recurrencia es poco probable tras la corrección del problema primario.

Primer episodio documentado

En ausencia de una causa aguda, existe un grupo de pacientes que, por primera vez, ha presentado un episodio de FA, tanto si su terminación ha sido espontánea como si se ha efectuado una intervención terapéutica para ello. No conocemos el comportamiento futuro de la enfermedad

FA recurrente

Cuando existen dos o más episodios de FA documentados

FA paroxistica

Episodios de duración inferior a 7 días, en general inferior a 24 h, en los cuales la arritmia termina espontáneamente o después de administrar algún fármaco antiarrítmico

FA persistente

Episodios no autolimitados de más de 48 h, precisando intervención terapéutica para su finalización

FA permanente

De larga duración, habitualmente más de un año, que no revierte a ritmo sinusal, o recurre a pesar del tratamiento

B1. Cardioversion farmacológica. Aunque muchos casos de FA paroxistica cardiovierten de forma espontánea en las primeras 24 h, la utilización de fármacos antiarrítmicos favorecerá la reversión a ritmo sinusal. Los fármacos de elección en pacientes sin cardiópata estructural son los antiarrítmicos del grupo IC (flecainida y propafenona) por vía oral o intravenosa, ya que son eficaces, bien tolerados y con bajo riesgo de proarritmogenia. Durante su administración se debe monitorizar la presión arterial y el electrocardiograma, pues pueden ocasionar conversión de la fibrilación auricular en flutter, con posibilidad de conducción 1:1. No se deben administrar si existe disfunción sistólica de ventrículo izquierdo, insuficiencia cardíaca, isquemia aguda, o trastornos importantes de la conducción intraventricular. En pacientes con cardiopatía estructural se utiliza amiodarona intravenosa.

No se debe realizar cardioversion si el tiempo de evolución de la FA es supenor a 48 h (o si la duración es incierta) sin estar previamente anticoagulado. Puede realizarse en aquellos casos que tras la realización de un ecocardiograma transesofágico se haya

excluido la presencia de trombos auriculares, realizándose el procedimiento con heparina intravenosa, manteniendo la anticoagulación al menos 4 semanas después del procedimiento.

Ante un paciente con fibrilación auricular paroxistica o persistente de menos de 48 h de evolución, se debe intentar la reversión a ritmo sinusal, inicialmente mediante cardioversion farmacológica, y si no es eficaz mediante cardioversion eléctrica. En caso de inestabilidad hemodinámica, se realizará cardioversion eléctrica directamente. En el caso de que hayan pasado más de 48 h, o sea de inicio incierto, se debe anticoagular y controlar la frecuencia cardíaca, para, posteriormente, programar una cardioversion eléctrica (al menos tras 3 semanas de anticoagulación).

B2. Cardioversion eléctrica. Es eficaz en la mayoría de los casos, sobre todo si la duración de la FA es inferior a un año.

Con frecuencia, la cardioversion eléctrica se hace de modo electivo en pacientes con FA persistente. No obstante, puede ser necesario realizar una cardioversion urgente en aquellos casos en los que la arritmia sea el principal responsable del deterioro

hemodinámico (insuficiencia cardíaca grave, hipotensión, agravamiento de la angina). La cardioversion se lleva a cabo con el paciente en ayunas y con sedación con fármacos de acción corta (propofol, midazolam), de modo que el paciente pueda recuperarse en un corto tiempo y pueda ser dado de alta. La descarga eléctrica debe sincronizarse correctamente con el QRS, lo que exige la elección de una derivación en la que se registre un complejo QRS de magnitud adecuada. La energía inicial transmitida con una forma de onda monofásica es de 200-300 J. En caso de desfibriladores con onda bifásica la energía requerida es menor. La cardioversion eléctrica está contraindicada si existe intoxicación digitálica, ya que puede provocar taquiarritmias ventriculares de difícil control.

C. Prevención de recurrencias en la FA paroxistica y en la persistente cardiovertida

Aproximadamente el 50% de los pacientes en los que la FA se revierte a ritmo sinusal recurren durante el primer año de tratamiento antiarrítmico (con frecuencia en el primer mes de tratamiento). Se asocian a recurrencia de la FA la edad avanzada, la insuficiencia cardiaca, la dilatación de la aurícula izquierda y la duración prolongada previa de la FA.

En la actualidad se considera que el objetivo del tratamiento con fármacos antiarrítmicos debe ser, fundamentalmente, mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes, ya que no ha demostrado un efecto beneficioso sobre su pronóstico. Por tanto, el tratamiento farmacológico antiarrítmíco para el mantenimiento del ritmo sinusal debe limitarse a pacientes con episodios de FA frecuentes y mal tolerados clínica o hemodinámicamente. El efecto secundario más frecuente es la proarritmia, que prácticamente no se presenta en pacientes sin enfermedad cardiaca subyacente. En los pacientes jóvenes y sin cardiopatia estructural se deben utilizar los fármacos de clase IC (flecainida o propafenona) como primera elección, eventualmente asociados a un beta bloqueante. Si estos fracasan, se puede ensayar el sotalol, reservando la amiodarona para casos

refractarios, por su perfil de toxicidad durante la administración prolongada. En pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica pueden utilizarse el sotalol o la amiodarona. En los pacientes con cardiopatía estructural la amiodarona es el fármaco más seguro y eficaz. El sotalol puede ocasionar alargamiento del QT y arritmias ventriculares polimórficas, especialmente al inicio del tratamiento y si existen factores predisponentes (insuficiencia cardiaca, alteraciones electrolíticas, QT prolongado, sexo femenino). Por ello es recomendable que el inicio del tratamiento se realice en el hospital, con monitorízación del ritmo cardiaco.

La ablación del nodo AV, con implantación de un marcapasos Wl. está indicada en pacientes muy sintomáticos y refractarios al tratamiento. En los últimos años se está desarrollando una nueva técnica para la prevención de las recurrencias de la FA, que consiste en la ablación de las venas pulmonares. Con los datos actualmente disponibles, podría indicarse en pacientes jóvenes sin cardiopatía estructural, con FA que no ha respondido a otros tratamientos, en quienes la FA parece estar relacionada con un foco automático auricular localizado cerca de las venas pulmonares.

Otra alternativa en la prevención de la FA es la estimulación eléctrica, que consiste en la estimulación bicameral con determinados algoritmos de estimulación para prevenir ta FA. En los pacientes con síndrome taqui-bradicardia, estaría indicada la estimulación

eléctrica bicameral para prevenir la recurrencia de la FA. y el marcapasos para evitar la bradicardia.

Otros procedimientos menos utilizados son los abordajes quirúrgicos, como la técnica de MAZE que interrumpe las vías necesarias para mantener la FA y reestablece tanto el control de la frecuencia como la función mecánica. La técnica de MAZE se ha utilizado como cirugía primaria y también como procedimiento añadido en los pacientes sometidos a cirugía cardíaca por otros motivos.

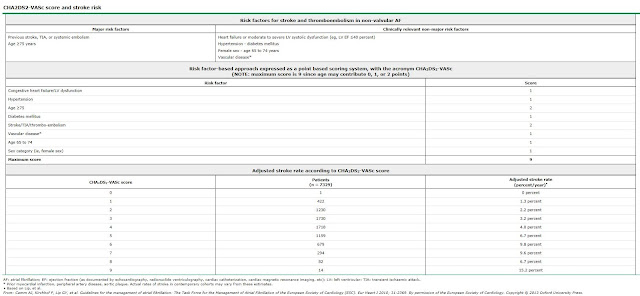

D. Prevención de las complicaciones embólicas

Indicada tanto en la FA paroxistica como en la FA establecida.

La FA es la causa más frecuente de embolia de origen cardiaco, y el 75% de las mismas se manifiestan como un accidente cerebrovascular. El riesgo es mayor al inicio de la FA y en el periodo pericardioversión. El riesgo embolígeno en la FA paroxistica y crónica

es similar. En consecuencia, se debe anticoagular a todo paciente con FA paroxistica (a partir del segundo episodio) y crónica, salvo que sea un paciente joven sin cardiopatía ni ningún factor de riesgo de embolismo. Para simplificar, se pueden diferenciar tres situaciones clínicas que pueden tener normas de prevención tromboembólica específicas o particulares:

1. Profilaxis en la cardioversion. Si la FA tiene más de 48 h de duración o no se conoce su fecha de inicio, se debe anticoagular con acenocumarol, manteniendo un INR entre 2 y 3.

durante 3 semanas antes y al menos 4 semanas después de la cardioversion. La indicación de anticoagulación crónica se decidirá en función de los factores de riesgo que presenle cada paciente. No se deben hacer diferencias en la pauta de anticoagulación entre el flutter y la FA; tampoco se deben hacer diferencias entre cardioversion eléctrica y cardioversion farmacológica. Se puede adoptar una estrategia alternativa mediante ecocardiograma transesofágico que excluya la presencia de trombos en la aurícula, pero manteniendo la anticoagulación un mínimo de 4 semanas tras la cardioversion.

Se puede realizar una cardioversion sin anticoagulación si la FA tiene menos de 48 h de evolución en los pacientes sin valvulopatía mitral ni antecedentes de embolia. Cuando se

deba realizar una cardioversion urgente es aconsejable iniciar tratamiento con heparina. Los pacientes que presenten una cardioversion espontánea a ritmo sinusal deben ser

manejados siguiendo las mismas pautas indicadas para la cardioversion.

2. Profilaxis en la FA asociada a valvulopatía mitral. Se debe anticoagular a todos los pacientes que presenten FA y cardiopatía valvular mitral: estenosis o insuficiencia mitral reumática, insuficiencia mitral degenerativa, prolapso de la válvula mitral y calcificación del anillo valvular mitral. Es conveniente mantener un INR de 2,5-3,5.

3. Profilaxis en la FA no valvular. Deben recibir anticoagulación oral (INR 2-3) los pacientes con uno o más factores mayores de riesgo embólico: edad > 75 años, HTA, insuficiencia cardiaca, FEVI < 35%. antecedentes embólicos y/o trombo intracavitario. En el caso de tener dos o más factores de riesgo embólico menores (edad > 65 años, diabetes, cardiopatía isquémica), también se considera un criterio de anticoagulación, con el mismo objetivo de INR. Por último, en los pacientes menores de 65 años sin factores de riesgo embólico asociados, se puede recomendar antiagregación con aspirina en

dosis de 300 mg diarios (Adiro* comp. 300 mg); en caso de contraindicación se utilizará clopidogrel (PlavixE comp. 75 mg) en dosis de 75 mg/dia.

En pacientes sin prótesis valvulares sometidos a procedimientos con riesgo de sangrado, como cirugía o endoscopia con biopsia, en los que es preciso suspender la anticoagulación oral, no es necesario instaurar otra terapéutica si el tiempo de interrupción de la profilaxis es inferior a una semana, aunque es una práctica habitual la administración de heparinas de bajo peso molecular (HBPM) a dosis de anticoagulación durante el periodo en el que se suspende la anticoagulación oral. En los pacientes con riesgo embólico muy elevado o en los casos en los que se prevea una suspensión superior a una semana, se debe indicar tratamiento con heparina fraccionada de bajo peso molecular. En los pacientes con intervenciones menores (p. ej., extracción dental), se debe sustituir la anticoagulación oral por HBPM en dosis de profilaxis (p. ej.. enoxaparina 40 mg/dia).

C. Prevención de recurrencias en la FA paroxistica y en la persistente cardiovertida

Aproximadamente el 50% de los pacientes en los que la FA se revierte a ritmo sinusal recurren durante el primer año de tratamiento antiarrítmico (con frecuencia en el primer mes de tratamiento). Se asocian a recurrencia de la FA la edad avanzada, la insuficiencia cardiaca, la dilatación de la aurícula izquierda y la duración prolongada previa de la FA.

En la actualidad se considera que el objetivo del tratamiento con fármacos antiarrítmicos debe ser, fundamentalmente, mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes, ya que no ha demostrado un efecto beneficioso sobre su pronóstico. Por tanto, el tratamiento farmacológico antiarrítmíco para el mantenimiento del ritmo sinusal debe limitarse a pacientes con episodios de FA frecuentes y mal tolerados clínica o hemodinámicamente. El efecto secundario más frecuente es la proarritmia, que prácticamente no se presenta en pacientes sin enfermedad cardiaca subyacente. En los pacientes jóvenes y sin cardiopatia estructural se deben utilizar los fármacos de clase IC (flecainida o propafenona) como primera elección, eventualmente asociados a un beta bloqueante. Si estos fracasan, se puede ensayar el sotalol, reservando la amiodarona para casos

refractarios, por su perfil de toxicidad durante la administración prolongada. En pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica pueden utilizarse el sotalol o la amiodarona. En los pacientes con cardiopatía estructural la amiodarona es el fármaco más seguro y eficaz. El sotalol puede ocasionar alargamiento del QT y arritmias ventriculares polimórficas, especialmente al inicio del tratamiento y si existen factores predisponentes (insuficiencia cardiaca, alteraciones electrolíticas, QT prolongado, sexo femenino). Por ello es recomendable que el inicio del tratamiento se realice en el hospital, con monitorízación del ritmo cardiaco.

La ablación del nodo AV, con implantación de un marcapasos Wl. está indicada en pacientes muy sintomáticos y refractarios al tratamiento. En los últimos años se está desarrollando una nueva técnica para la prevención de las recurrencias de la FA, que consiste en la ablación de las venas pulmonares. Con los datos actualmente disponibles, podría indicarse en pacientes jóvenes sin cardiopatía estructural, con FA que no ha respondido a otros tratamientos, en quienes la FA parece estar relacionada con un foco automático auricular localizado cerca de las venas pulmonares.

Otra alternativa en la prevención de la FA es la estimulación eléctrica, que consiste en la estimulación bicameral con determinados algoritmos de estimulación para prevenir ta FA. En los pacientes con síndrome taqui-bradicardia, estaría indicada la estimulación

eléctrica bicameral para prevenir la recurrencia de la FA. y el marcapasos para evitar la bradicardia.

Otros procedimientos menos utilizados son los abordajes quirúrgicos, como la técnica de MAZE que interrumpe las vías necesarias para mantener la FA y reestablece tanto el control de la frecuencia como la función mecánica. La técnica de MAZE se ha utilizado como cirugía primaria y también como procedimiento añadido en los pacientes sometidos a cirugía cardíaca por otros motivos.

D. Prevención de las complicaciones embólicas

Indicada tanto en la FA paroxistica como en la FA establecida.

La FA es la causa más frecuente de embolia de origen cardiaco, y el 75% de las mismas se manifiestan como un accidente cerebrovascular. El riesgo es mayor al inicio de la FA y en el periodo pericardioversión. El riesgo embolígeno en la FA paroxistica y crónica

es similar. En consecuencia, se debe anticoagular a todo paciente con FA paroxistica (a partir del segundo episodio) y crónica, salvo que sea un paciente joven sin cardiopatía ni ningún factor de riesgo de embolismo. Para simplificar, se pueden diferenciar tres situaciones clínicas que pueden tener normas de prevención tromboembólica específicas o particulares:

1. Profilaxis en la cardioversion. Si la FA tiene más de 48 h de duración o no se conoce su fecha de inicio, se debe anticoagular con acenocumarol, manteniendo un INR entre 2 y 3.

durante 3 semanas antes y al menos 4 semanas después de la cardioversion. La indicación de anticoagulación crónica se decidirá en función de los factores de riesgo que presenle cada paciente. No se deben hacer diferencias en la pauta de anticoagulación entre el flutter y la FA; tampoco se deben hacer diferencias entre cardioversion eléctrica y cardioversion farmacológica. Se puede adoptar una estrategia alternativa mediante ecocardiograma transesofágico que excluya la presencia de trombos en la aurícula, pero manteniendo la anticoagulación un mínimo de 4 semanas tras la cardioversion.

Se puede realizar una cardioversion sin anticoagulación si la FA tiene menos de 48 h de evolución en los pacientes sin valvulopatía mitral ni antecedentes de embolia. Cuando se

deba realizar una cardioversion urgente es aconsejable iniciar tratamiento con heparina. Los pacientes que presenten una cardioversion espontánea a ritmo sinusal deben ser

manejados siguiendo las mismas pautas indicadas para la cardioversion.

2. Profilaxis en la FA asociada a valvulopatía mitral. Se debe anticoagular a todos los pacientes que presenten FA y cardiopatía valvular mitral: estenosis o insuficiencia mitral reumática, insuficiencia mitral degenerativa, prolapso de la válvula mitral y calcificación del anillo valvular mitral. Es conveniente mantener un INR de 2,5-3,5.

3. Profilaxis en la FA no valvular. Deben recibir anticoagulación oral (INR 2-3) los pacientes con uno o más factores mayores de riesgo embólico: edad > 75 años, HTA, insuficiencia cardiaca, FEVI < 35%. antecedentes embólicos y/o trombo intracavitario. En el caso de tener dos o más factores de riesgo embólico menores (edad > 65 años, diabetes, cardiopatía isquémica), también se considera un criterio de anticoagulación, con el mismo objetivo de INR. Por último, en los pacientes menores de 65 años sin factores de riesgo embólico asociados, se puede recomendar antiagregación con aspirina en

dosis de 300 mg diarios (Adiro* comp. 300 mg); en caso de contraindicación se utilizará clopidogrel (PlavixE comp. 75 mg) en dosis de 75 mg/dia.

En pacientes sin prótesis valvulares sometidos a procedimientos con riesgo de sangrado, como cirugía o endoscopia con biopsia, en los que es preciso suspender la anticoagulación oral, no es necesario instaurar otra terapéutica si el tiempo de interrupción de la profilaxis es inferior a una semana, aunque es una práctica habitual la administración de heparinas de bajo peso molecular (HBPM) a dosis de anticoagulación durante el periodo en el que se suspende la anticoagulación oral. En los pacientes con riesgo embólico muy elevado o en los casos en los que se prevea una suspensión superior a una semana, se debe indicar tratamiento con heparina fraccionada de bajo peso molecular. En los pacientes con intervenciones menores (p. ej., extracción dental), se debe sustituir la anticoagulación oral por HBPM en dosis de profilaxis (p. ej.. enoxaparina 40 mg/dia).